How Formula 1 Expertise Is Shaping Our New Family of Electric Vehicles

Up until the early 1970s, the automotive industry followed a single path for gas vehicles: More power meant a bigger engine, resulting in more weight, more cost, and, in most cases, worse fuel efficiency.

But then came the fuel crisis in the mid-1970s, which resulted in an innovative new device that could deliver both power and the fuel efficiency customers were suddenly demanding — the turbocharger. While the first automotive applications appeared in 1962 for racing, the technology truly began its journey toward the mainstream in 1973 with the debut of the BMW 2002 Turbo, proving that smaller engines could punch well above their weight.

It seemed to defy physics — using a new device that turned wasted energy into power for more compression to make a smaller engine behave like a much larger one. In 2011, Ford introduced its version of the turbo, EcoBoost, on the F-150 pickup truck in the U.S. Ford’s bet was that turbos would redefine the industry, including the F-150, even as others were skeptical of customer adoption.

Sales skyrocketed, and the industry followed suit: Now, nearly 75% of F-150 trucks are sold with turbocharged engines,1 and nearly all our gas-powered vehicles offer it.

Today, the industry faces a similar challenge with electric vehicles, where the engineering solution for range anxiety has mostly been to increase the size of the battery in the vehicle. But the battery is the most crucial component to tackle affordability because it accounts for somewhere around 40% of the vehicle’s total cost and upwards of 25% of its total weight.

Just like when automakers simply made bigger engines, adding more battery makes the vehicle heavier, more expensive, and creates a massive physics challenge.

Our big bet for electric vehicles? Obsessing over the vehicle as a system to get more miles out of a smaller battery and radically simplifying the system to reduce the number of parts so we can deliver a new family of affordable electric vehicles to driveways around the world.

Affordability is not a marketing tagline for us. To truly make vehicles built on this platform affordable, starting with a mid-size electric truck, we needed to hunt down the cost opportunities.

We started by creating a team within the skunkworks operation, tasked with developing range, efficiency, and performance metrics for priorities such as weight, drag and rolling resistance, and ultimately battery size. That team armed every engineer with a new way of evaluating tradeoffs — we call them bounties.

Historically, engineers in traditional automotive companies can be siloed in departments that match the component or system they are assigned to. They’re expected to advocate for the part they are working on while decreasing its cost, often without the context of understanding how it impacts the customer’s experience or performance of the vehicle.

For example, the aerodynamics team always wants a lower roof for less aerodynamic drag; the occupant package team wants a higher roof for more headroom, while the interiors team wants to decrease the cabin size to reduce the cost. Usually, these groups negotiate until they find a middle ground, one that inevitably ends in a tradeoff led by yet another department tasked with making tradeoffs on behalf of the customer.

Bounties change the negotiation, making the true cost of a tradeoff much clearer by connecting it to a specific value tied to the range and battery cost. Now, the aerodynamics team and interior team share the same goal, and both understood that adding even 1mm to the roof height would mean $1.30 in additional battery cost or .055 miles of range. With bounties, each team has a common objective to maximize range while decreasing battery cost — a direct linkage to giving our customers more.

This is just one example of countless bounties our team focused on. When we met targets, we would set more difficult ones to challenge ourselves further. One of these areas was our energy management system.

An electrical architecture is the blueprint for how power and signals move through a product — what connects to what, how everything is controlled, and how it all works together reliably. Power conversion within an electric vehicle platform can account for a surprising amount of wasted energy in a vehicle while charging or even taking energy from the 400V battery and converting it to 48V for the low-voltage devices.

More importantly, it’s often segregated into functions that get sourced to external suppliers, each with their own enclosures, fasteners, and connecters, which drives high costs and excess weight into the platform.

So in 2023, we moved our high-voltage power electronics architecture and design for this platform in-house. With the acquisition of Auto Motive Power, or AMP, talented engineers joined our team with experience, pushing the limits of power conversion and energy management for numerous global electric vehicles already on the market today.

For the first time, customers will experience a fully electric vehicle charging ecosystem designed in-house by Ford using our own software. That means the hardware in the vehicle, including the bi-directional charging capabilities, comes from a team directly integrated into the one working on the platform and vehicle products. Customers will benefit from improvements that decrease the amount of time waiting around for the battery to charge, maximize the lifespan of the battery, and decreases in total cost of ownership.

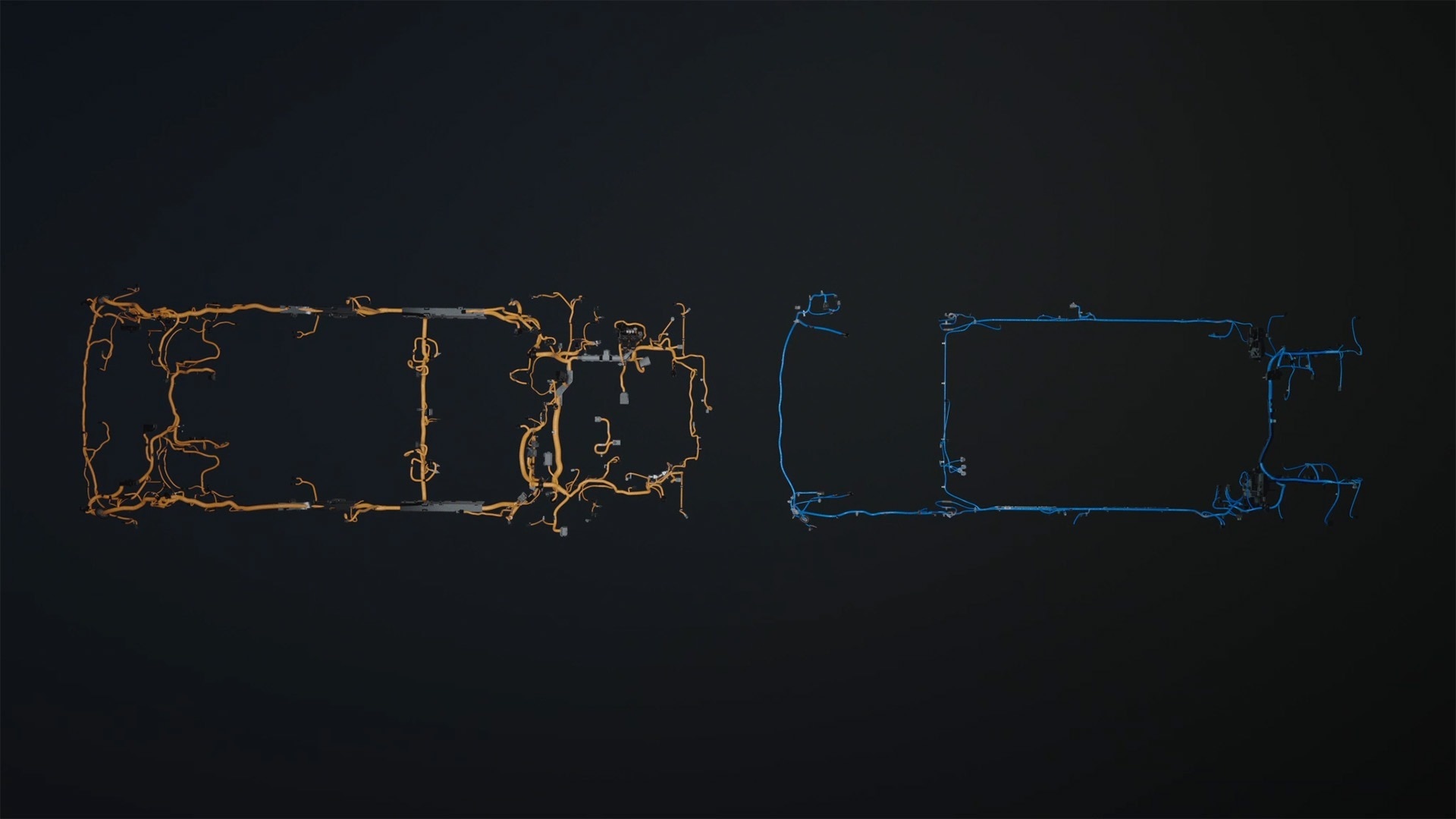

The team’s work has had profound improvements beyond just developing Ford’s first 48-volt low-voltage system. In fact, this new hardware and software have played a key role in making the mid-size electric truck's wire harness 4,000 feet shorter and 22 pounds lighter than one of our first-gen electric vehicles.

We know there will be skeptics, just like there were when Ford introduced the turbo on the F-150. Other companies will claim that they've tried much of this before. But physics isn’t proprietary. We're creating a truly integrated electric vehicle platform, not a single part that can be easily copied.

If we succeed, we will have a family of vehicles that we expect to compete on price with the best in the world, including gas vehicles. There’s still a lot of work to do, but we’re making progress, and we can’t wait to share more soon.

Alan Clarke is executive director of Advanced EV Development at Ford.

1Based on 2025 CY industry-reported total sales of F-150® EcoBoost® V6 engines and F-150® 3.5L PowerBoost® Full Hybrid V6 engine vehicles.

We are utilizing a true systems engineering approach across design, product development, software engineering, supply chain and manufacturing. This collaborative effort completely rethinks vehicle production, with every decision centered on reducing battery size and delivering more value for money to customers.

We are moving to a zonal architecture where multiple vehicle functions are integrated into a small number of modules. This is a significant shift from conventional vehicles, which typically use over 30 scattered Electronic Control Units (ECUs) from various suppliers, leading to complex wiring, weight, and higher manufacturing costs.

Our platform combines functions into 5 main modules, substantially reducing the wiring harness’s cost and complexity. We also transitioned from a 12-volt system to a 48-volt system, which allows for thinner copper wires. These changes collectively made the mid-size electric truck’s wire harness 4,000 feet shorter and 22 pounds lighter than one of our first-generation electric vehicles, recognizing that weight is a major problem for efficiency. We are also using higher speed ethernet to allow our modules to communicate effectively and properly distribute edge computation.